How They See #37 with Joanna Sitnik-Van Hasselt on art conservation

When I created How They See, I desired to give space not only to artists but also to other people present in the art domain. Curators, collectors or art conservators are people who can also be interesting and enrich the view on art. Hence my guest in this issue of How They See is Joanna Sitnik-Van Hasselt, an art conservator.

Preserving works of art was for a long time a real mystery for me. How to match the colour with the original one? How to approach a hundred-year-old painting, which is a priceless cultural heritage, to preserve it and not destroy anything? I also noticed that I was perceiving an art conservator profession differently. It was quite a discovery to learn that chemistry is a very important science to master and how valuable is the research of the artwork or consultation before actually starting any work. After all, I have found answers for those and other questions in my interview with Joanna and on her Instagram profile. The latter is also full of information and insights useful for all artists (oil paints and turpentine!).

To find more about Joanna, you can visit her Instagram profile or website.

I hope this interview will spark some interest in this, and other art related topics :) In the meantime How They See is going for Easter holidays and will be back on 10/04.

Dear readers, I would like to wish you a peaceful Easter break. Stay healthy in this difficult times!

I have a feeling that an art conservator is like a surgeon and NASA scientist connected in one person. Some time ago I watched a documentary about the restoration of a painting by Mark Rothko, devastated by someone in London. I was surprised that the process needed so much preparation.

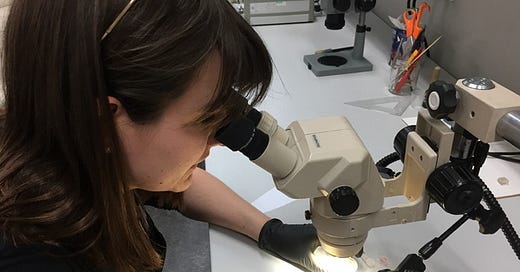

Well, conservators need broad education and knowledge, because what most people see is the “after effect”, but it involves a lot of research, documentation, examination and practical work. We use a lot of technologies and equipment that were originally developed or built for something else, for example rtg or infrared spectroscopy. Of course, certain conservators specialize in certain areas, but in general, a good conservator should understand all the aspects that I mentioned.

It was also interesting to me, that there are plenty of intricacies. Sometimes, even using the most advanced techniques, you can’t match the colours at 100%.

To be honest, to match the colour at 100%, you don’t need advanced techniques, it is a matter of good eye and experience :) Advanced techniques and technologies help more with for example research or cleaning/removing varnish.

What is the most difficult part of being an art conservator…

It’s hard to say what exactly is the most difficult part of my job. I think it depends on a certain project. Sometimes it can be a specific problem/treatment that is the most difficult. Another time it’s the complexity of treatment, and sometimes more practical things - working with strong solvents can be quite risky and exhausting.

…and what personal traits are making this profession easier?

Broad interests – technology of art, chemistry, history of art, artistic skills etc. All those are valuable to be a good practising conservator. Patience is also important, although it is a different type of patience – the ability to work in detail. Personally in life, I am the opposite of patient, but at work, I can work for hours and hours on one painting. Another important thing is the ability to think outside of the box, because none of the projects is the same so sometimes it is necessary to be creative with the treatment ideas.

I was also wondering how you approach art objects that need conservation works. Do you have a to-do list or are there any good practices that allow the whole process to be generalized?

There are some steps that you have to follow. For example, before I even start tests, I take good photos of the object. In general photography, documentation is very important at every stage of work. Then I proceed to the tests, an examination that will tell me what is the problem, how the painting is built, how to approach it. Every object should be treated individually, like a patient, although there are some general rules that can guide us through the treatment.

And what about your emotions? I mean, you are standing in front of a very old, priceless painting and you have to renovate it. Any mistake could be irreversible.

When I get the object I mostly feel excitement about the new project, new challenges. Of course, sometimes there is stress. But in those moments it is especially important to do everything patiently and slowly to be 100% sure of what you do. Every single step conservator takes should have very good arguments - why do you do it, why do you use these materials, not others. Very often problems are discussed between colleagues, a few conservators, to be really sure if the chosen treatment and methodology is the best for the painting. If you have a good and confident answer for all those kind of questions, there is no place for mistakes :) And at the end of the project, it is pure joy and pride. I’m not gonna lie, I’m very proud of a lot of my projects, especially those that hang in world-known museums or institutions.

How often paintings need to undergo treatment done by an art conservator? What does it depend on?

Oh, that can depend on many things. Ideally, we do the treatment that doesn’t need to be repeated any time soon, but of course, it depends on where the painting is stored, how the owner takes care of the painting after treatment, what is the technique of the artist, etc. Sometimes, even though the materials are tested and well examined, it happens that after for example 20 years, the material behaves in an unexpected manner. For example, in the 80s keton-varnishes were often used, for sure with the best intent, but now we see that you have to remove it because over the years there is a risk it becomes irreversible.

Does the art conservator’s code of ethics help in such cases?

Conservator ethics is very important and is a guideline for us. Every specialized conservator with a diploma knows this. For example, all the materials we put on the works of art have to be reversible, or we cannot overpaint or add anything to the original artist’s vision.

By conserving a painting, you discovered that it was a fake. How should art conservators behave in such a situation?

First, talk to the owner. It is the owner who decides what to do with it further. I always share my knowledge and my evaluation with the owner, but I am not the one who decides what to do with it, because it is not my possession.

I read on your Instagram that you need very good eyesight for this job. It’s a bit like an aeroplane pilot. Do you have to undergo any special medical examinations to work in this profession?

It doesn’t require such a good eye as a pilot, but for example, I was advised against an eye operation (vision correction), because it may reduce the ability to see subtle differences between colours. During studies, we had to have health examinations, because of the risk of working with solvents and on the height of scaffolding.

Apart from paintings, you also deal with the conservation of photographs. At first glance, these are two different worlds.

Yes, those are two totally different words. I was always passionate about old photography, and I did experiment a lot with it myself. I wanted to learn a lot about the conservation of photography as well, so I signed up for an additional course during studies that later on evolved in the subject of my diploma work. It does require a different approach and different skills.

In your QA on Instagram, people often asked about the most difficult object you worked with. I will try to rephrase this question: what is more challenging, working on objects from museum catalogues or private collections?

My most common answer to this kind of question is “it depends” :-D Museum objects are challenging because of the value they carry – both artistic and their worth. On the other hand, those are kept in very good conditions, so conservation challenges are often more complicated in private collectors’ cases (if the object wasn’t stored properly or has a very complicated history). But of course, this is a generalization.

Suppose you have been allowed to work with any art object you can dream of. What would you choose?

Jan Van Eyck painting. Because he is a master of masters for me. And seeing exhibitions of his paintings live in Ghent made a very big influence on me.

Last year, I talked to Łukasz Wiącek about creating an art collection and that it is always worth considering buying an original work. Are there any general rules to follow when hanging a painting at home? What is the best way to take care of it?

Yes, there are a few rules that collectors should follow. For example, keeping it in a stable condition, without very big temperature and humidity fluctuations, or not hanging it in direct sunlight. The best way to take care of a painting is to give it to a conservator with a diploma if it needs any kind of treatment, instead of trying to take care of it yourself.

Which period in the history of art are you most passionate about and why?

I don’t have one specific favourite time because I love something of all the periods – I love the technique of renaissance and baroque painters, the decorative aspect of art nouveau and the free spirit of contemporary art.

What is your favourite colour?

Gold, dark red, navy-blue and ultramarine :)